From super scoopers to super sleuths, the arsenal

to prevent FOD has new entries.

Separated from its coffee-cup companion, a plastic cap propelled by jet exhaust haphazardly careens across an airport tarmac. To most people, this urban tumbleweed is an irksome, but harmless, traveler on today’s landscape.

To an aviation professional, such litter is anything but harmless. It is FOD. And whether the acronym stands for foreign object debris or foreign object damage, FOD can kill when ingested by an aircraft.

Unfortunately, FOD is all too prevalent in aviation. It is found on manufacturing lines, in maintenance shops, on airport ramps, and in skyways. Its innumerable forms include wire clippings, solder balls, hardware, tools, luggage parts, crumbling concrete, construction debris, ice, salt, birds, electrostatic discharge, and more.

“By definition, FOD is a substance, debris, or article alien to a vehicle or system which would potentially cause damage,” explained Andrew Kenney, secretary and public affairs officer for National Aerospace FOD Prevention Inc. (NAFPI). Besides its deadly potential, FOD costs about $4 billion annually in aircraft repairs, NAFPI said.

Born to fight FOD

In the war against FOD, NAFPI is a key resource. Formed in 1985, this nonprofit educational organization has more than 500 members who represent military groups, aircraft and engine manufacturers, airlines, airports, and FOD prevention suppliers. Member-ship is free, and all NAFPI directors are volunteers to the cause.

“NAFPI objectives are to make the industry aware of the need to eliminate FOD and to provide information about current proven practices and technological advancements regarding awareness, detection, and prevention,” Kenney said.

One of NAFPI’s major contributions is an annual conference, and this year’s gathering is scheduled for August 7-9 in Amarillo, Texas, and will be cohosted by Bell Helicopter Textron. The conference has grown quickly in recent years, expanding from 300 participants and 15 exhibits in 1994 to about 700 participants and 35 exhibits in 2000.

The 2000 conference also featured 19 interactive learning sessions, hosted by industry volunteers who shared their experiences with FOD prevention, tool control, failure analysis, and more. Another highlight was a tour of the Kennedy Space Center by the conference’s cohost, United Space Alliance (USA), to demonstrate USA’s FOD prevention program as it applies to different space-shuttle processing environments.

NAFPI also publishes a FOD prevention newsletter four times per year and hosts a website (www.nafpi.com) containing FOD-prevention guidelines, NAFPI’s membership directory, and links to FOD-prevention representatives and vendors. NAFPI’s board members also work year-round with companies, associations, and government agencies to prevent FOD.

In the war against FOD, awareness and prevention programs are mandated weapons. However, they must go well beyond preaching “clean as you go” to aviation maintenance technicians. The problem of FOD is broad in scope, so any effort to prevent it must also be broad. For example, sources for this article said that some of the worst FOD polluters are people who never lay a hand on an aircraft component, like food services, luggage handlers, refuelers, and construction crews.

United’s new FOD program.

One airline that has significantly expanded its FOD program is United Airlines. Although it has long practiced FOD prevention, United began giving the topic increased attention two years ago, after launching several strategic initiatives.

One initiative sought to reduce all aircraft damage by 65 percent within five years. “Understanding that FOD is a portion of aircraft damage and an increasing safety concern, we decided to elevate our resources to address this issue,” said Alex P. Orosz, United’s FOD program manager.

“As I attacked this FOD problem, I noticed two major deficiencies. First, there existed no truly accurate method to assess all FOD events, how they affected operations, what fleets were involved, or how much FOD cost United.

“Second, while all of United’s line stations performed some type of FOD prevention, each was unique; some stations instituted excellent FOD pro-grams while others were essentially ineffectual.”

In 1999, Orosz developed a computer program that searches United’s maintenance database for “hard FOD” or wildlife-strike incidents. From the responses, Orosz eliminates non-FOD events and duplicate reports of a single FOD incident, to create an accurate database of FOD incidents.

“With this compilation, we record information such as dates and aircraft tail numbers, descriptions of discrepancy write-ups and subsequent maintenance performed, man-hours dedicated to the repair, along with material costs and operational effects,” Orosz said.

“We can also analyze locations where incidents occur to determine where there may be a problem with hard FOD or wildlife. As I discussed this program with my colleagues from other air carriers, the Air Transport Association, and the United States Department of Agriculture [which has an interest in FOD caused by bird strikes], I realized that no one is tracking and reporting FOD and wildlife events as carefully and accurately as we are, except perhaps the military.”

To address inconsistency within FOD programs among United stations, Orosz revised various United documents so that each employee who works around an aircraft has specific written duties and responsibilities toward FOD prevention and that auditing measures are implemented.

“This way all line stations can follow the same protocol when performing FOD walks during dispatch or receipt of aircraft. In addition, I ensure that each and every gate has a bucket that is clearly identified for FOD usage only,” he explains.

Orosz’s FOD program has four main points:

-

Continual education and training so that all aircraft workers understand what FOD means and how to prevent it;

-

Dissemination of items that increase FOD awareness, such as decals, posters, pens, coffee cups, and other inexpensive incentives that workers can use each day, yet will continually remind them of FOD;

-

Instituting a recognition program that rewards employees who go above and beyond expectations in FOD recovery; and

-

Fostering greater airport involvement in preventing FOD.

“This final step requires that I meet with airport operations supervisors to ensure that not only are the taxiways and runways inspected and swept on a regular and frequent basis, but that the airport management champions monthly meetings where all other tenants, including nonairlines, attend,” Orosz said. “At these venues safety issues and FOD prevention methods are discussed amongst all airport tenants. Only with the involvement of every tenant at all of our airports will we finally be able to conquer the FOD problem.”

Products, websites, and pamphlets

Another notable FOD warrior is Gary Chaplin, president of The FOD Control Corp. His company supplies vacuum and magnetic sweepers, lost-tool finders, small-parts organizers and debris cans.

Another notable FOD warrior is Gary Chaplin, president of The FOD Control Corp. His company supplies vacuum and magnetic sweepers, lost-tool finders, small-parts organizers and debris cans.

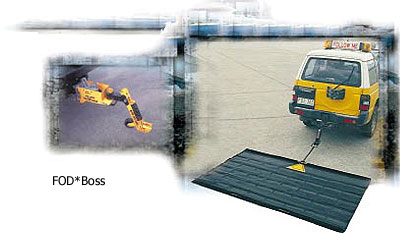

A new product Chaplin raves about is the FOD Boss Rapid Response Speed Sweeper, invented by Australian firm Aero Tech and distributed by The FOD Control Corp. The sweeper looks like nothing more than a flat rectangular panel that glides just above the airport surface.

However, the FOD Boss is said to proficiently sweep an eight-foot-wide swath, using no motor, magnets, or hydraulics. Instead the sweeper uses friction and kinetic energy, plus special brushes and scoops to pick up ferrous and nonferrous objects on wet, dry, and textured surfaces.

It is lightweight (62 pounds) and can be towed by any vehicle. The FOD Boss works at speeds between four mph to 25 mph, and it is small enough even to sweep under aircraft. Two FOD Bosses, connected side by side, can sweep nearly two million square feet in one hour.

“It picks up pretty much anything two inches in diameter or smaller,” Chaplin said. “We went to Delta’s top clean station and they couldn’t believe how much the FOD Boss picked up. It is really a good tool.”

Chaplin’s enthusiasm for this product and his company’s other FOD prevention products is rivaled by his goal to “provide all the products and information that the aviation industry would require to carry out their FOD prevention programs,” he said.

His fervor was fueled by a recent study by an Air Force lab at Wright Patterson AFB that discovered a profound lack of communication about FOD prevention, ideas, and solutions among all military branches. This prompted Chaplin to host a free, FOD discussion forum on his company’s website.

“We haven’t received the participation we hoped for, maybe because it is on a company’s website,” Chaplin acknowledges. “So we are developing an independent website, called fodnews.com. It will contain FOD news, articles, incidents, resource links, and conference information.”

“We haven’t received the participation we hoped for, maybe because it is on a company’s website,” Chaplin acknowledges. “So we are developing an independent website, called fodnews.com. It will contain FOD news, articles, incidents, resource links, and conference information.”

Chaplin also hired a professional writer to create a comprehensive booklet containing FOD-prevention guidelines, and he plans to publish a “full-on” book about creating a FOD-prevention program and keeping it going.

“The main point of the new website, new booklet, and book is: If you can’t get your management to understand FOD and know what it is costing, then you can have all the sweepers you want, and I’m just another guy selling sweepers.”

|

FOD Prevention Methods and Technologies |

|

|

– Aircraft and engine designs that are more resistant to FOD entrapment and damage-Boeing was cited by several sources for excellent work in this regard. – FOD awareness and prevention program-Online guidelines are available from NAFPI (www.nafpi.com), Boeing (www.boeing.com) and The FOD Control Corp. (www.fodcontrol.com). – Tool control methods, such as organizing tools using shadow box kits, engraving tools to identify their ownership and bringing to a job only those tools needed for the task-Suppliers exhibiting at NAFPI’s 2000 conference were Danaher/Matco, Kennedy Manufacturing, Kipper Tool, LISTA International, Jensen Tools/ Stanley Vidmar, Sears Industrial Sales, and SNAP-ON Industrial. – Aircraft and engine designs that are more resistant to FOD entrapment and damage-Boeing was cited by several sources for excellent work in this regard. – FOD awareness and prevention program-Online guidelines are available from NAFPI (www.nafpi.com), Boeing (www.boeing.com) and The FOD Control Corp. (www.fodcontrol.com). |

-Tool control methods, such as organizing tools using shadow box kits, engraving tools to identify their ownership and bringing to a job only those tools needed for the task–Suppliers exhibiting at NAFPI’s 2000 conference were Danaher/Matco, Kennedy Manufacturing, Kipper Tool, LISTA International, Jensen Tools/ Stanley Vidmar, Sears Industrial Sales, and SNAP-ON Industrial. – Runway sweepers and vacuums-Sources exhibiting at NAFPI’s 2000 conference were FOD technology, The FOD Control Corp., MADVAC International, and TYMCO. – Borescopes to inspect jet engine intakes. Sources exhibiting at NAFPI’s 2000 conference were Everest VIT, Gradient Lens, and Olympus America. – FOD-retrieval devices-Sources exhibiting at NAFPI’s 2000 conference were FOD Technology, The FOD Control Corp., and Olympus America. – Miscellaneous materials, like protective covers, trash barrels, and signs to highlight FOD awareness. Sources exhibiting at NAFPI’s 2000 conference were Checkers Industrial Products and FCE Industries. |

Detective work

For his book, Chaplin is enlisting the help of another well-known FOD fighter, George Morse, president of Failure Analysis Service Technology (FAST). FAST’s contribution to FOD prevention is sleuth work to determine what caused a FOD incident.

“For years, we’ve treated FOD as a people problem, but FOD prevention goes beyond that, because what happens when a fastener breaks off and is ingested by the engine? ‘Clean as you go’ doesn’t take care of that problem,” Morse said.

“Also, a good percentage of FOD incidents, maybe 75 percent, go into a category of ‘unknown’ as far as the cause. Other times, people think they know the cause, but really don’t, so they end up using resources to address a problem that didn’t cause FOD, while overlooking the problem that did. “Before any solution is implemented, we need to find out what actually caused the FOD. We perform the FAST test, which can analyze any component to determine the cause of impact damage.”

For the test, a piece of tape is pressed against a damaged part, to collect microscopic particles left behind by the FOD source. The tape is sent to FAST, which performs the analysis.

Morse gives an example of the test’s value. An Air Force jet underwent repair of FOD damage to its first stage turbine. During the next flight, the same engine experienced FOD damage, this time to the compressor.

It was assumed that the maintenance crew did not repair the engine properly and the same type of FOD caused both incidents. But the FAST test proved that the second incident had nothing to do with the first. The turbine was damaged by concrete debris, while the compressor was damaged by a rivet from the aircraft.

“As to FOD causes, more times than anything else, I see aircraft fasteners, new and broken. For commercial airline customers, I also see a fair amount of luggage hardware,” Morse said. “On the other hand, we are seeing less and less construction debris, mainly because airports are requiring construction crews to receive FOD training before they start working.”

Seeking human factors

Once again, the human plays a pivotal role in FOD prevention. This brings us to another FOD-fighting tool: research funded by the FAA’s Office of Aviation Medicine to delve into which human factors contribute to FOD and which factors hinder it. This project, being conducted by Galaxy Scientific, is part of a wider, multiyear effort by the FAA to analyze human factors that affect aviation maintenance and inspection.

The project began by assessing the current state of FOD research and prevention, and by analyzing FOD prevention programs obtained from various industry partners. The second step includes developing a FOD mishap definition and analysis databases to determine FOD trends.

The third step will assimilate data related to the annual cost of FOD. And the fourth step will study data from multiple industry partners to look for “significant differences” in FOD trends and investigate their current FOD strategies.

“Though FOD-prevention programs currently exist, there seems to be little evidence that these programs were developed based on a well-developed need analysis,” said Felisha Mason, engineering specialist and the project’s point of contact at Galaxy. “This project will address that gap by identifying potential contributory root cause factors that lead to FOD and by developing a series of recommendations and/or corrective actions based on generalized human-factors knowledge and current industry best practices.”

Thus, the battle to prevent FOD gains new strength. Apply all the tools well and that plastic coffee cap cavorting along the ramp doesn’t have a chance.

|

NAFPI’s FOD-Prevention Program Ingredients |

|